This is Context Rot

I swear I'm not like other newsletters.

The purpose of Context Rot is to help all of us, including me, make sense of an increasingly bewildering and fast-changing digital world.

Here’s how it’ll work: most days, I’ll share news, thoughts, and commentary on the state of AI, technology, and living online. Sometimes there will be longer essays.

My goal is to not only keep you up to date with what’s actually important in the crowded world of technology news, but also have a point of view—something I think is often missing from tech writing. I won’t be afraid to be critical when I believe it’s warranted, and I work in tech, so I know what I’m talking about and can offer nuance and insider information you won’t find elsewhere.

At the very least, I’m confident I can give you some weird shit to talk to your coworkers about.

And now, your context:

Everyone is being super normal about GPT-5

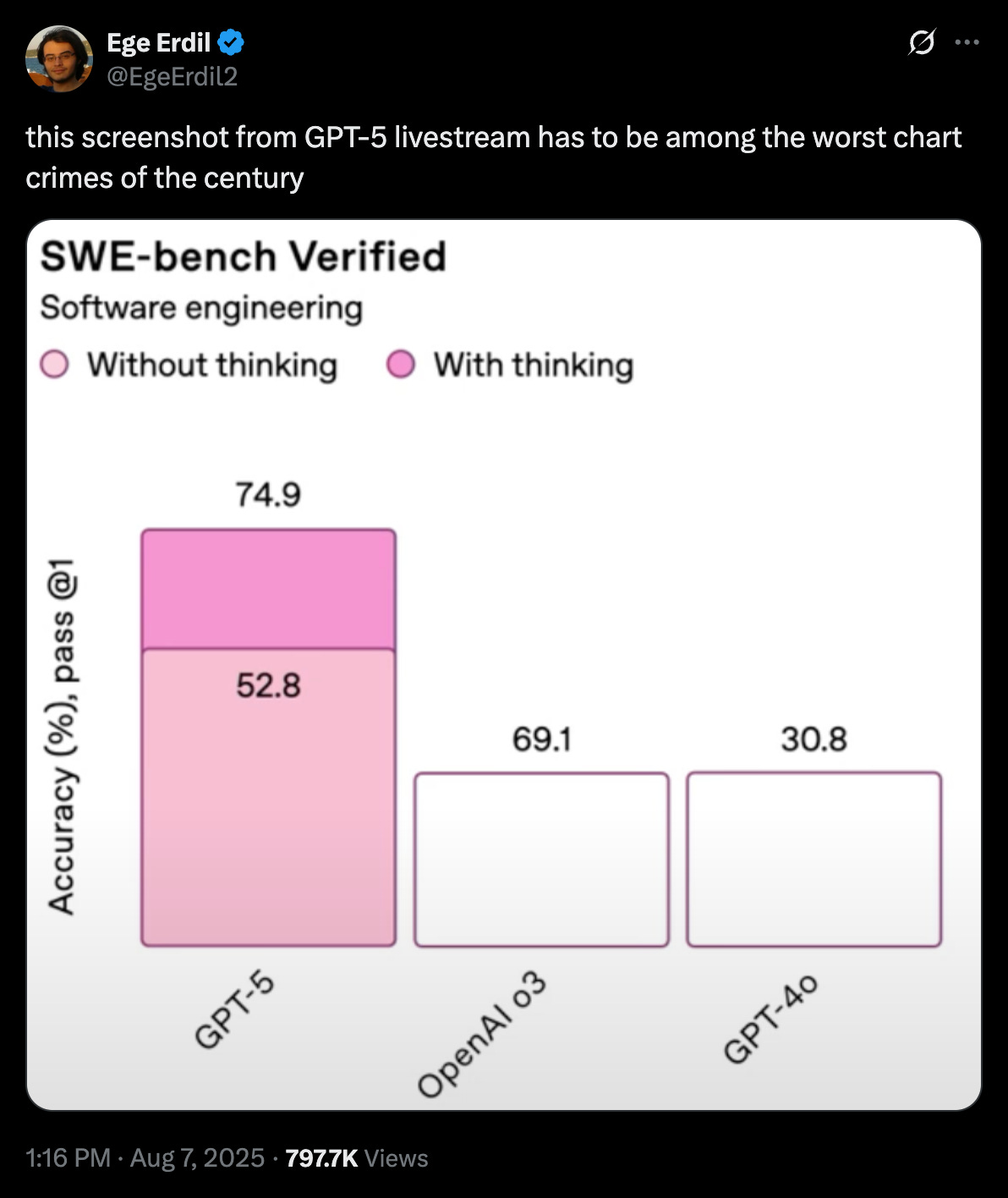

Last week, OpenAI released GPT-5, its latest foundational AI model. It beats out the company’s previous models in most categories, notably in software engineering. While illustrating this point, OpenAI showed off several graphics during their announcement livestream that don’t make any sense, but what do we (humans with eyes) know.

What I found more interesting is that after the release, OpenAI updated the ChatGPT app to remove the older models (including GPT-4o, the prior default), and people got very, very angry at them. A lot of users also felt something less expected: loss.

LLMs are not traditional consumer products. A lot of users form deep attachments to these AI models (this will be a recurring theme in the newsletter), so removing their access can feel more like robbing someone of a friendship than simply deleting a software feature that someone enjoyed. OpenAI eventually rolled back this change and made the older models available again in the ChatGPT app.

Is this… healthy? Unclear. What it should be, though, is less surprising to a company like OpenAI. There are many examples from recent years of what happens when you suddenly change the personality of an AI companion, and I think this demonstrates a large blind spot that Sam Altman and the rest of the company have. There are two primary customers of OpenAI: developers using their APIs to build products, such as customer support bots or AI-enabled software development platforms, and people who chat with the models through the ChatGPT app. Often these people are just looking for answers to questions or help with something at work, but sometimes they’re also looking for support, feedback, guidance, or just companionship.

One of the reasons that people open the ChatGPT app instead of going to Google when they have a question is because of the AI’s personality, and the relationship that the user develops with the AI over time. Again, the jury is very much out on whether the connections that many users form with ChatGPT are a good (or just, like, ok) thing, but OpenAI needs to do a better job of understanding this because it’s not going away.

No, 75% of all OpenAI use is not students cheating

A chart went viral on Twitter/X a few days ago that seemed to show “OpenAI usage” declining abruptly by about 75% over the course of two days in June. It was immediately quoted and shared all over the place with the theory that as soon as school let out (which is not a thing that happens on one single day nationwide), everyone stopped using ChatGPT.

But the graphic is not from OpenAI, it’s from a company called OpenRouter, which makes a product that allows you to easily switch between AI models—so you can e.g. replace a call to ChatGPT 4.1 with a similar one to Claude Sonnet 4 if you hit a usage cap or want to test something out. All that the chart actually means is that the volume of calls on OpenRouter for OpenAI models dropped, which seems to have just happened because of a change they made where you could enter your own API key instead of using theirs (if you don’t know what this means don’t worry about it).

ChatGPT usage, meanwhile, has continued to grow.

People get very upset when you slop on main

Justine Moore, an investor at A16Z, recently posted a seemingly innocuous AI generated video of a “frappucino” being “made.” It wasn’t particularly impressive, realistic, or beautiful, but it had that good old fashioned AI slop quality of being completely anodyne in a brain-smoothing way. It’s something you could watch on repeat a few times on your TikTok feed in bed. Justine invests in AI products, seems to enjoy playing with them, and is often posting things like this.

But this particular post escaped containment, and was met with a kind of insane backlash (as is typical on the internet, it didn’t help that Justine happens to be a woman). I’m not highlighting this to dunk on Justine, nor do I think that making fun of an obsession with generating these videos is problematic, but the degree of vitriol here is indicative to me of just how much a lot of the internet hates AI, which isn’t usually included in the broader narratives about its impact. It’s a theme I’ll be talking a lot about.

Keep your slop to yourselves, I guess. Or just post it on YouTube or Facebook, they love it over there.

From the doomscrolls

I really liked this Derek Thompson piece about how the technological boom of the late 1800s/early 1900s also caused people to lose their minds (“diseases of the wheel” and “American Nervousness” are bangers). Uber founder Travis Kalanick is doing vibe physics. RFK’s latest enemy is a potential cure for cancer. The kids are maybe actually not okay, or at least they’re getting meaner (?).